Edgar Allan Poe is, of course, one of America’s most iconic writers. Many credit him with inventing or popularizing multiple literary genres, including mystery, horror, and detective fiction. But the real Poe has become distorted over the years – transformed by fans into a dark and tortured soul obsessed with alcohol and death.

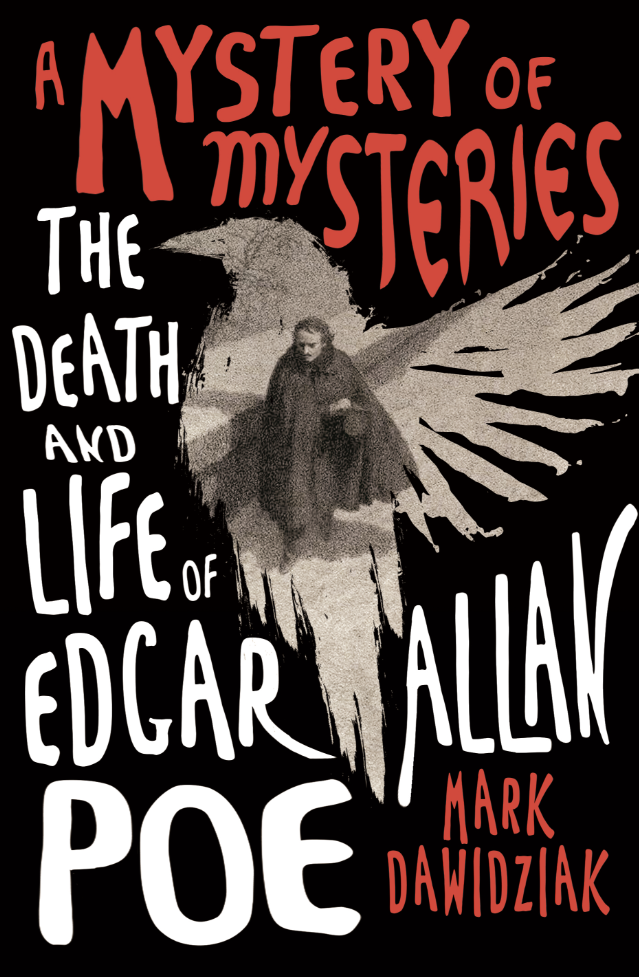

My guest is author Mark Dawidziak, and his new book is called “A Mystery of Mysteries: The Death and Life of Edgar Allan Poe”. He not only shares with us what Poe was really like, but also walks us through some of the many theories surrounding Poe’s agonizing death in a Baltimore hospital in October of 1849. He also talks about possible explanations for Poe’s mysterious three missing days – just before he was discovered, delirious and in another man’s clothes, at a Baltimore polling-place.

More about the author’s prolific work at his website, here: https://www.markdawidziak.com/

Connect with the author through Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/mark.dawidziak

The Interview Transcript:

Erik: Hello and welcome everyone to another episode of the Most Notorious Podcast. I’m Erik Rivenes, back again, and I am so pleased to have Mark Dawidziak as my guest today. He is a former adjunct professor at Kent State University and the former television critic for The Plain Dealer in Cleveland, 43 years in journalism. And he is the author of a great many books including Mark Twain for Cat Lovers, The Bedside Bathtub Armchair Companion to Dracula, which is a title I love to say, Everything I Need to Know I Learned in the Twilight Zone and a bunch more, and he has a new book officially out February 14th, 2023. It is called A Mystery of Mysteries, The Death and Life of Edgar Allan Poe. And it is so great to have you on the show. And Poe is one of those figures who’s so iconic. He’s known as the father of Gothic literature. But right away in your book, you set the record straight. Poe was not, in fact, this dark, scary, hermit-like character that many people today want to believe he was.

Mark: Yes, exactly. It’s one of the reasons I wrote the book. It’s certainly one of the primary reasons was to sort of rescue Poe from the caricature we’ve made of him. And that caricature, as you alluded to, is this kind of sickly, hollow-eyed guy up in an attic, you know, with a raven perched on his shoulder, huddled over a manuscript with a bottle of cognac at his hand and a red-eyed black cat prowling in this dusty attic. And it was nothing like that. I mean, that is the caricature. That is the stereotype of Poe. And if you say Edgar Allan Poe to most people, they probably wouldn’t think of something quite that extreme. But that is kind of where they’re going overall is this this “master of the macabre” this “grandfather of goth” guy and in truth that was part of who he was I mean, I’m not trying to say he wasn’t you know drawn to those things. But it’s a small part of what he was. He was a very versatile very complex writer and a very dedicated writer. He was, you know, I think that some people like Poe to be writing these stories out of these kind of fever dreams and, you know, maybe under the influence of stimulants of some kind. And that’s not true. He was a very exacting, very careful writer. He was, you know, in many ways, America’s first professional writer. The first writer who really tried to completely make his living, not that he was entirely successful at it, but to completely make his living as a man of letters by writing and editing. And in the 1800s, most writers had other jobs, they were either independently wealthy, or they taught, and they were at universities, or they had their government jobs. Poe tried to at a time when there were no copyright laws and there was very little protection and very little money for what he did, he tried to exist by pushing nouns against verbs and it’s a very brave thing. To do that, you have to be, you can’t be under the influence of alcohol all the time. Poe had a problem with alcohol, there’s no question, but what that problem was that he was probably allergic to it. By all accounts, it took very little alcohol to get him roaring drunk. He would down one glass of wine and it would be like he’d been drinking all night and then he paid for it. It would take him days to recover. It would have a tremendous effect on his system. Poe’s problem with alcohol is that he drank at the wrong times. He always seemed to pick the worst time to get drunk when it would do him the most harm and it would have the worst effect on his career. What most people are surprised to learn about Poe is that, I always love when somebody says oh you’re writing – Edgar Allen Poe is my favorite author, I love everything is written and I always want to say – everything really? And when they say everything they what they mean is they have one of those complete tales and poems collections and they read all of it, which is not inconsiderable and that’s what is wonderful but you know I don’t say out loud but part of my brain is going really, you read all 17 volumes? And if you did say that they probably look a little shocked at you as well. Poe only was 40 years old when he died. And yet he found enough time to write enough really highly polished copy to fill 17 volumes. And only a small tiny fraction of that is horror. That little tiny fraction has completely defined Poe to us today. And that’s where the caricature, that’s one of the places the caricature comes from. Fame has been a double edged sword for Mr. Poe. While on the one hand, those stories have kept him alive, because he was so good. I mean, Poe wasn’t the only person writing gothic stories during that period. It was a big industry. All the magazines back then were filled with it. He was just that much better at it. He was so miles ahead of everybody else. And today, his reputation is defined by that handful of horror stories and the poems, which actually also fall in this, was like The Raven and Annabelle Lee and The Bells, the poems that sort of fall on the spooky side of the street. So we’ve made Poe into this – that that has completely defined him for us today. And I think Poe would be delighted to know that he was still remembered all these decades later. And I think he at the same time, he’d be a little bit appalled to know – oh, but yeah, you’re gonna be remembered, but it’s only for these this this handful of stories – I think he would be a little appalled at that because he would have said, you know If you had said to Edgar Allan Poe, oh, you’re a horror writer. He wouldn’t have even known what that meant. They didn’t have that term! (Both chuckle) If you all the great people who wrote horror and took her to new levels in the 19th century. Mary Shelley, Poe, Robert Louis Stevenson, Bram Stoker, not one of them thought of themselves as a horror writer like we know it today. They said, well, you know, if a horror story is the best way to tell the story, that’s the way I’m going to do it right now. But you know, like with Stevenson, Stevenson would have said, Well, today I’m writing Treasure Island. Tomorrow, I’m writing Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. The next day, I’m writing A Child’s Garden of Verses. And the next day I’m writing essays because that’s what the mood takes me. And Poe was that kind of writer. Poe’s writing is amazingly versatile, and it covers a lot of different forms. So yes, he was a great horror writer. Yes, he invented the modern detective story, with his Auguste Dupin stories. Yes, he was a poet, but he was also not primarily known in his lifetime for any of those things. He was primarily known as a critic, a literary critic, and one whose standards were so exacting and so high, he was nicknamed the Tomahawk Man. And he believed America’s literature would never grow up and escape the influence and the impact of particularly Great Britain but other countries unless it found its own voice. Poe held his known nation’s literature up to the highest standards and he wasn’t liked for it at all. Most people didn’t – but the amazing thing is how good a critic Poe was because his judgments hold up. If you go back and look at the people he praised, it’s Nathaniel Hawthorne, it’s Washington Irving, the people he praised have lived and the people he dismissed deserve to be dismissed and you wouldn’t recognize their names today. So Poe is in his lifetime, is known primarily first and foremost as a critic, secondarily as a poet, and third, as the writer of stories of horror and mystery. Our time has reversed that order. To us, Poe is primarily known as the author of short stories first, a poet second, and if you know it, critic third. But certainly everybody is always amazed when I tell them that Poe wrote as much humor as he did horror. Nobody thinks of Edgar Allan Poe as a comedy writer. But Poe was a witty guy. He was very funny. He’s actually very funny in the horror stories. Some of the horror stories are very, very funny. You have very funny moments. And he was not who you think he was. He was very courtly, very charming. He was a southern gentleman. You know, did he have a bent for the melancholy? Did he dress in black? Did he? Did he have those elements of him that sort of patterned after his hero, Lord Byron? Yes, yeah, that’s part of who Poe is. But it’s just part of who he is. And that’s one of the reasons I wrote the book was to sort of expand our view of Poe. We don’t lose Poe as the Master of the Macabre. When Twain, Mark Twain in the 1960s was primarily known as a humorist and a family author. And when we found out that he was also a great social critic, and all these suppressed writings came to light, we all of a sudden start to see Twain in all of these other ways, which we didn’t see him. It didn’t take away Twain, the humorist and Twain, the family author. So it’s not going to take away Poe, the horror legend, by acknowledging all these other things that he was, as a matter of fact, you’ll come to a greater understanding of how he wrote those horror stories and why he was so good at it. If you acknowledge the other complexities that made up who he was.

Erik: His photograph as well, right? People connect with Poe through one particular photograph that was taken in the last year or two of his life, when his health was on the decline and he wasn’t taking good care of himself. And it really wasn’t what Poe looked like for most of his life.

Mark: That’s another thing which has muddied the record and has also strengthened the stereotype of Poe. Poe was born in 1809 and he died in 1849 at the age of 40. We only have eight known photographs, what were called daguerreotypes, and then maybe three or four authenticated portraits, watercolors and such that were done in his lifetime. We have only these handful of images of Poe. I mean, you compare it to say, Mark Twain. If Poe had lived a few more years, we would have hundreds of photographs of him. But we only have these eight photographs and these handful of portraits. And the one that’s the oldest, the one that goes back the most is 1843. So all of the photographic or image evidence of Poe and what he looked like come from the last six years of his life, which means we have 34 years which are undocumented. So, and these six years are the six years when he’s going to go in decline. He’s going to look increasingly more haggard, increasingly more sickly, and it’s the last few photographs from the last two years of his life which are the most famous. If I say Edgar Allan Poe, you get an image of Poe, and you go back to one of the images from where that idea of Poe comes from, it’s from those last two years of his life. He didn’t even wear a mustache until the last two or three years of his life. So if you encountered Poe on the streets of Philadelphia in the early 1840s, and you think you would have recognized Poe, because “I know what Poe looks like”, he probably would have passed you right by, and you wouldn’t even know who it was, because he either had sideburns, no mustache. He would have been moving at a brisk almost military pace because he had been in the army. He would have been looked very hale and healthy. He stood very erect and if you met him, you would meet this probably very courtly with a Southern gentleman type and with a great sense of humor a little bit self-deprecating. Does any of that sound like the Edgar Allen Poe you think you know? But right, but that’s who he was. That’s that’s exactly who he was. So yes, the photographic record hasn’t helped him either. If Poe had lived into the late 19th century, and the advent of what we call the Kodak, which was the candid photograph, where anybody could take pictures of their friends and families, anybody could have a box camera and take pictures, family pictures. We would have images of Poe laughing, smiling, playing in the front yard, playing leapfrog and playing leaping contests and winning by the way because he was very athletic. We would have all of these pictures which would probably forever change our image of who he was. We have none of that. All the pictures were taken in studios and people didn’t smile for photographs back then, because it was hard to maintain a smile for the length that the camera lens had to stay open. So we would have, you know, all the pictures tend to be a little bit unsmiling and grim, and very serious. And that’s what we have of Poe. That’s the image we have of him. So yeah, that’s another thing which is sort of contributed to this very limited view we have of Poe.

Erik: Yeah. You mentioned this earlier, and I want to ask you before I forget, you talked about Poe creating one of fiction’s first detectives. And even Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, right, credited him…

Mark: Completely! On several occasions. Right. Conan Doyle was asked many, many times about the influence of Poe. He gave a speech on the 100th anniversary of Poe’s birth, crediting Poe. And he gave the speech to a room of mystery writers. And he basically, you know, acknowledged the fact that we’re all living off of what Poe created. Poe didn’t create the mystery story so much as he created the model for the master detective. And his C. Auguste Dupin is the direct model for Sherlock Holmes and Hercule Poirot and so many detectives who are going to follow. And Conan Doyle gave him full credit for that. There are only three Dupin stories. That’s it. This is, “The Murders in the Rue Morgue”, “The Mystery of Marie Rogêt”, and “The Purloined Letter”. And those three are the basis on which all of the master detective stories emerge from. And it’s quite amazing. It’s you know, I always think it’s fun to think that the two guys who sort of pushed detective fiction into different ways, both have profound Baltimore connections. Poe does this and creates the, essentially something that’s going to be co-opted by the Brits, is this master detective. And then who’s going to take that to other extremes? Well, it’s going to be Conan Doyle and Agatha Christie and Dorothy Sayers and people like that. And then in the 1920s, you have another guy who has Baltimore connections, Dashiell Hammett, basically taking the detective story and pushing it into the very realistic American hardboiled direction. And so you have – and I always like the fact that both Poe and Hammett, Hammett was born in Baltimore, and Poe died there. And they’re both known for literary birds. Poe’s Raven and Hammett’s Maltese Falcon. Well, how good is that? (Both laugh) You have these these these two birds staring at each other and leading the way in. What is the the two great directions of detective fiction.

Erik: Yeah, and on that same note, this is something you mentioned in your book, John Douglas, the famous FBI agent, thinks that Poe’s detective may have been the first behavioral profiler in history.

Mark: You know, and some people think it’s overstated, but I think if John Douglas says it, it gives it a lot of credence. Because John Douglas is the pioneering FBI agent in the area of profiling. So I, you know, that’s pretty credible evidence for giving Poe credit for being not only the father of the modern detective story, but also perhaps for a great area of forensic investigation. I don’t think it’s overstating it. It fits, and there are things which always sort of cross over with Poe. Poe doesn’t sort of segment his writing. He’s the same writer, no matter what he’s writing. And one of the things that Poe does in his horror writing, one of the reasons his horror writing is still as good today, and it’s still as gripping today, is because Poe is incredibly insightful when writing about the psychology of the characters that he’s talking about. He gets deep down into the neuroses and the fears of his narrators. The mistake that most people have made in studying Poe over the years is to confuse Poe with his unreliable narrators. That was a tendency to actually be taught in the classroom. Coming out of the French who admired Poe greatly like Baudelaire. When I was in high school, there was this kind of idea that Poe was drawing on himself to create all of these, the narrator of The Raven, or the narrator of the Telltale Heart, or the narrator of the Cask of Amontillado. That’s a very simplistic way to look at it. It’s also shortchanging Poe as an artist. He wasn’t those guys. Was he was a he was a drawing on things of his life? Yes, but that’s what every writer does. He and he wasn’t though, one of those obsessed narrators, that and but that’s another thing that’s contributed to again the stereotype. But Poe is an acute observer of human nature and So that’s that that feeds his criticism. It feeds his poetry. It feeds his mystery stories. It feeds his horror stories and that’s why he’s a good profiler. That’s why he would have been a good profiler. And that’s what John Douglas sort of keys in on when he talks about the way Poe went about assembling his crime stories. So that’s why I think, yes, I think that’s evidence that had to go in to the book. A lot of people like to claim Poe. Science fiction people, there are elements of Poe’s stories that science fiction fans like to claim. I think it’s true, but I don’t think Poe’s science fiction is anywhere near as, you know, he’s going to influence Jules Verne. Jules Verne acknowledged Poe’s influence. So I think there is an indirect influence on later writers. But he does have a tremendous influence on an awful lot of very different types of writers later on. You know you you would imagine he’s going to influence people like Conan Doyle on the mystery side or H.P. Lovecraft on the horror side and he does they both acknowledged poe’s dead But would it surprise a lot of people to learn that F. Scott Fitzgerald? You cited poe is a great influence That doesn’t seem to fit, does it? But yet, he did. So Poe’s influence is immense on a lot of different forms.

Erik: Yeah. So you state in your book that it can be difficult piecing together an accurate biography of Poe’s early life because he liked to embellish when talking about his childhood and some aspects of his adulthood. Would you tell us more about his early life?

Mark: Sure. Poe is the son of actors, and this was a time when the acting profession was very difficult. If you were an actor, you were an itinerant actor, you had to travel from city to city in order to make a living. You were required to learn a lot of parts, commit a lot of different parts to memory. You lived surrounded by squalor and disease. The accommodations for actors in different towns were very poor and cheap, and the theaters were very rickety. It was a very difficult lifestyle, and you were asked to do everything. If you were not actually acting on the stage, you were going to be setting up set pieces or taking tickets at the box office. It was a very arduous, difficult life. And both of Poe’s parents were actors. His mother was a very good actor. His father was a very bad one. But from his mother, he got this incredible work ethic. She had memorized a staggering number of roles, comedy, Shakespeare, melodrama, she could dance, she could sing. She was this dynamo. So I think Poe got his artistic sense and his work ethic from his mother. Also, actors were considered just one step up from prostitutes in that age. That was the era where a nickname for the theater was the Legs of Satan. And so actors were looked at as a pretty immoral bunch and don’t let your daughters near an actor type of thing. And Poe, who had pretenses of being a Virginia aristocrat, as an adult this is one of the most admirable things about him. He never disowned his parents. He always said he was proud of being the son of actors, particularly of being his mother’s son, of being the son of this well thought of, beloved actress. But Elizabeth Bowe, his mother dies. Very young. Edgar was about three years old, when his mother dies. And most accounts put him at the deathbed as she was dying in Richmond. He was born in Boston. His parents were in Boston at the time. So he’s born in Boston. And then his mother had – was was performing in Richmond. When she took ill, she lingered for a few months and then died of tuberculosis. Poe is not adopted. He’s taken in by a wealthy Richmond merchant named John Allen and his wife, who do sort of treat him for a while as their son. And you would think that they would have adopted him, but no, he was always a foster child. He was never, never formally adopted by the Allens. But it’s where his middle name comes from. It’s where the Allan of Edgar Allan Poe comes from. But he is raised basically as a Southern gentleman. And when John Allan comes into a lot of money, Poe’s expectation is if he inherits just a small part of that fortune, which would, it would certainly have been logical of him to assume that he would, he would have been quite well off. And instead, John Allan leaves him nothing, basically never adopts him and leaves him absolutely nothing. And I think this creates quite a yearning in Poe that is never quite fulfilled for the rest of his life. He’s always kind of this outsider insider. He’s always this guy who’s granted access to the circles of – the inner circles of literature and power. And yet he’s never of them. He’s never accepted by them. He’s never fully accepted by them. So, you know, Poe right from the start, is denied an awful lot of things, not the least of which is the love of, of parents that he desperately needed. So he’s damaged goods right from the get-go. Now, I say all that and it’s kind of easy to cast John Allan as a villain in Poe’s life, and from Poe’s perspective, he certainly was. And also from anybody who sympathizes with Poe’s perspective, it’s hard to work up any great affection for John Allan. However, John Allan did us a great favor by not leaving Poe any money. He didn’t do Poe any favors by disinheriting him, but he certainly did us a great favor because had Poe inherited the money he expected to inherit, he probably would have lived out his life as a gentleman poet. He would have pursued writing poetry, maybe some essays and letters, and that would be it. We probably would not know the name Edgar Allan Poe today. Instead, because he was cut off, he had to find a way to make a living and he had to pursue forms of writing which he wouldn’t have pursued otherwise. He certainly wouldn’t have pursued the short stories because there would have been no economic need to write for magazines that wanted that kind of fare. So Poe in the 1830s starts to write short stories, and he starts to write stories which we would call horror tales. We probably wouldn’t have gotten that Edgar Allan Poe. So every Poe fan in some way begrudgingly, ought to thank John Allan for not giving him any money. Because otherwise, we wouldn’t have the mystery stories and we wouldn’t have the horror stories. And who knows if he would have reached as deep as he did psychologically to write the great poems that he did. So I, you know, Poe’s life goes off the rails, kind of. He goes to the University of Virginia, Charlottesville. He stays there for, you know, less than a year and he falls into drinking and this is the first real bouts of drinking. Even here, the classmates who remember him remember him just charging down, not savoring the drink or just charging it down and immediately being inebriated. The record and the witnesses of the effect of alcohol had on – the devastating effect that it had on Poe is documented almost right from the start. But he racks up gambling debts, he goes back to Richmond, he fights with John Allan, he goes to Boston, publishes his first volume of poems in the city of his birth, and it is credited to a Bostonian, and he joins the army. He joins the army under an assumed name Edgar Perry. And he is sent to Fort Moultrie on Sullivan’s Island in South Carolina, and which is going to become the setting for The Gold Bug, one of his great mystery stories. And he eventually leaves the army and manages to get himself admitted into West Point. Same problems at West Point as there was at the university where he doesn’t have enough money and John Allan won’t give him enough money to support what he needs to live at West Point, and also the discipline at West Point didn’t quite fit his personality, so he conspires to get himself court-martialed, and he does, which is not odd by the way, a lot of people dropped out of West Point. They’d get there and it was a lot harder than they thought it was going to be. It was a lot more disciplined. The cadets weren’t even allowed to play chess or cards in their dorms. There was just this very, very spartan, strict code at West Point. And so Poe drops out, he goes to New York, and then he ends up in Baltimore, he drifts into Baltimore, and it’s here in Baltimore that he finds with the Poe family that was there, his relatives. He finds the first sense of belonging. He moves into the house that his aunt, who was affectionately known as Muddy, Mariah Clem, he moves in with them. He with Mariah is her daughter, Virginia. And as Virginia gets older, Poe falls in love with her. And he gets a job in the Southern Literary Messenger in Richmond. And he is away from Muddy and Virginia. He’s living in Richmond and he’s desperately lonely for that family. And he proposes marriage to Virginia. Virginia is only 13 at the time and that always shocks people of course. It does sound shocking. You can’t gloss over that one or speed by it because he does marry his 13-year-old cousin. Back then it would not have sounded as icky in the mid-1830s as it does now. There were a lot of people who married their cousins back then and young women, girls, got married almost as soon as they were eligible. That happened, but Poe was obviously a little sensitive to this because he fudged her age on the marriage certificate. He did seem a little leery about that, but they become a family. And he now probably going to enter into this phase of this career in Richmond and then into Philadelphia, this golden age where he starts to write the short stories. And he starts to write the material into the early 1840s, for which we are going to best remember him for. So that’s the kind of the nickel tour that gets him to, you know, finally, he’s in Philadelphia for a few years and then he comes to New York in the mid-1840s and the last five years are spent in New York. Virginia dies at the Fordham Cottage and that’s where Poe’s life really falls apart. When Virginia dies, the last few years of Poe’s life is very chaotic. And his health is also – he’s obviously deteriorating. And all you have to do is look at the, if you look at the pictures of Poe from the last two or three years, and you look at them in order, you’re looking, it becomes a picture of a man who’s falling apart and is obviously has some kind of very serious health issues.

Erik: Yeah. It was around the time that he was in the army that he really started to split from his foster father, John Allan. Allan always preached independence and Poe was needy and Poe would write these letters confronting his foster father, calling him out on various things about his neglect, etc. There’s some resentment there. And then at the end of the letter, he’d almost inevitably ask for money, right?

Mark: You know, there are things about Poe that just drive you nuts. And that’s one of the things he does is he can, he writes letters, which are ultimately insulting and pleading. And he always – there’s this veiled man on the ledge, you know, love me or I’ll jump aspects to some of this pleading. He often is, he doesn’t quite come out and say it, but there’s this notion of, well, if you don’t send money now, this will be the last you’ll ever hear of me or, more to your shame, because, you know, and he’s either hinting at suicide or that his health is so precarious that he’s not going to make it. And very melodramatic. I mean, here’s the son of actors right now in some of these letters. He’s playing to the balcony in some sense, but he’s also desperate. Some of the times you see him – when he leaves West Point, he’s living in New York. He is very sick when he’s in New York, and he’s got almost no money, and he’s starving. So just the littlest bit from John Allan would have helped him a great deal. John Allan had illegitimate children he left money to, then he didn’t leave any to Poe. It really is an extreme case. He really did work up an act of dislike for this foster child. From John Allan’s standpoint Poe was ungrateful, From Poe’s standpoint John Allen was distant. And he admired independence, but the only reason John Allan ended up with money is his uncle died and left him a fortune. John Allan didn’t do it from his great skill as a businessman. In fact, he nearly went under as a businessman. And none of that wasn’t his fault. A lot of it had to do with economic realities of the time. It had to do with things that were happening internationally. It wasn’t his fault, but the truth is John Allan probably liked to view himself as a self-made man, but he wasn’t a self-made man. He inherited his money. He inherited his fortune. Poe probably sensed the hypocrisy of all that, too. It was not a good matchup, you know, and once again, if it had been, we probably wouldn’t be talking right now.

Erik: Yeah, yeah. So I’d like to go back for a moment to his his marriage to Virginia. Of course, the views on relationships like this, they were different in the mid 19th century. But But as you’ve said, Poe himself, saw potential for scandal in marrying Virginia. Were there people around him disturbed at all by the fact that she was only 13? And as you state in your book, the idea of marrying the first cousin wasn’t so out of the ordinary, but even then, marrying a girl of that age raised eyebrows.

Mark: Yes. And again, you know, there’s there’s also a question of what the relationship was, you know, and that’s one of the things too, is that I, in this book, I’m trying to be very, very careful about not speculating. Um, the biographer always has to use the words probably, likely, perhaps, a lot – even in well documented lives you have to resort to those words because there are aspects of everybody’s life and personality which remain hidden. And we can’t – you can’t know everything and pose life is not a well documented life. There are many, many days and weeks we don’t have any records of- it’s like, again, if Poe had lived a few more years, we could have had him live a very well-documented life. Twain’s life is very well known. We know where Twain was almost every single day of his life. We know what he was doing, where he was. There are letters, there are constant letters. The record, and Twain is born in 1835. Poe is born in 1809. The difference of those years is the difference between a very badly documented life and a very well documented life. So Poe creates a lot of challenges for the biographer, and one of the things I think you need to do is resist speculating. There has been no end of speculation about the nature of the Poe’s marriage. Some believe it was never consummated. Some believe that their relationship was more brother and sister than it was husband and wife. What Poe really wanted was a family, a supportive family and two adoring, loving people. And he got that. Virginia and her mother, they did support him emotionally and did give him the sense of stability he probably needed above all other things. But there’s a certain point where the door is closed on the Poes’ bedroom. There’s a certain point that nobody gets to look into that and know the exact nature of their relationship. You know, perhaps it started out one way and then she got older. It became an actual marriage. We don’t know. And there’s no good authority to tell you exactly what it was. What we do know is he loved her deeply and she loved him deeply. And for as long as it lasted, because, you know, she dies very young, also of tuberculosis. For as long as it lasted, they were quite devoted to each other. And the people who visited the family in the year, if they visited them in New York or Philadelphia or wherever they happened to be living at the time, the picture of the Poe family is a very happy one, a very devoted, three people very devoted to each other. Four, if you count the cat, Katerina, who was part of the household for most of that time. But Poe’s wife dies in January of 1847 at the age of 24. So she’s almost still a child when she dies. She’s just made it to being a young woman, really. Well, we can think of as a young woman at 24. And, you know, his grief is overwhelming. So she dies in 1847. He dies in 1849. So he’s only going to live another two and a half years past Virginia.

Erik: Is her death, do you think, part of what begins his depression, his downward spiral?

Mark: Well, it is certainly I think the beginning of his deterioration, his rapid physical deterioration and also it doesn’t help that these are very chaotic years. Poe needs to have somebody in his life. He has a desperate need to have somebody to be taking care of him and I mean that emotionally. So he has his mother-in-law and as soon as Virginia dies, there is this string of flirtations, of romances where he’s obviously looking for the best possible candidate to replace Virginia in his life. And it’s not to say he was not really attracted to these women, but there is a desperation that you can sense as he’s going from one woman to another during these last couple of years. And trying to figure out what he really needs and what I think what he really wants is he wants the stability again of having this family structure. And I think that’s what he’s trying to replicate. I don’t know he’s looking for true love in all this point because the one person probably that he would have given up everything for was married. He was very good friends with Annie Richmond. This was the one that I think if she were available, he would have given up all the other pursuits for her and it was never going to happen because she was married, you know, and but he was, when we see what he writes about her, he writes about her with a passion that he doesn’t the other women. So, you know, this is a very chaotic couple of years. There’s a lot of feuds. He’s at his, you know, lowest in a lot of ways. It’s his most fallow period as far as writing is concerned. It’s one of his few periods when he doesn’t write that much because he’s physically incapable of it. He’s not writing horror, he’s not writing poetry, he’s not writing criticism, he’s certainly not writing humor. So he writes very little in this period and it isn’t until the last year, in the last year there’s this kind of renaissance. You know how people say when somebody is dying, they have this period where they have this bloom and they look healthier than they’ve ever looked. It’s almost like the beginning of the end. People say, oh! They look great. They look wonderful! Poe has this period where he starts to write again. He writes two really great short stories, both revenge stories, but he writes the Cask of Amontillado and Hop-Frog towards the end of his life. And he also had this kind of wonderful return to poetry at the end. The thing that he first fell in – his first love, and he writes The Bells and Annabelle Lee in this last period, which are two of his best two of his as matter of fact, you know, the Annabelle Lee is a posthumous poem. So he has this kind of you – when you think he’s washed up and you think he’s done, all of a sudden he comes back both with some short stories and some poems that show he still got it, he still got his fastball. And that’s so, so, there are indications that in that last year, when he seems to be at his worst physically, he’s bouncing back psychologically a little bit. It’s like one of the theories that has been put forth for his death, and there’s a lot of them, there’s more than 25 theories which have been put forth for what killed Poe. But suicide is always in the mix. And I don’t think so, because I think he actually is in a good place emotionally in the last year. At least in the last stretch from January of 1849 to October when he dies, of 1849, he’s got every reason to live, not the least of which is he finally looks like he might get the dream of his life, which is to own and edit his own magazine. That’s closest to being a reality during these months. One of the reasons he goes to Richmond in the summer of 1849 is to raise money for the magazine and to get subscriptions. He has a backer. He has somebody who’s willing to back him on this. So the Poe who leaves Richmond at the end of September and heads back north where his ultimate destiny is to get back to the cottage in Fordham in New York, that Poe has a lot to live for. So, you know, and the people who have studied Poe, you know, I cite in the book, people who have studied him, his psychosis as far as as a candidate for suicide, say he comes up very, very low. So suicide is one of the things that I would discount among the possibilities.

Erik: One of his great shortcomings, right, was his ability to make enemies out of friends. (Both chuckle) Why do you think he did this?

Mark: Poe wrote a short story called The Imp of the Perverse, and it’s about this human tendency to fixate on something perversely. And that it ultimately leads to an individual’s undoing, because they can’t stop obsessing about it. Poe was possessed of the imp of the perverse. There are so many points in his life where he not only picks the wrong time to start drinking, he picks the wrong time to pick a fight. And it’s like you want to reach into the pages of biography and slap him and say, no, no, no, no! This guy’s trying to help you!What are you doing? Poe had a lot of enemies. He made a lot of enemies. But the phrase “he was his own worst enemy” certainly applies to Poe’s life. He was very sensitive, like a lot of great writers are. He met Charles Dickens, and he precedes Mark Twain. All three of them were hypersensitive and nervous types. Poe is not an exception there, as far as literary genius of the 19th century goes, But he does have this tendency to pick the exact wrong time, to pick a fight and then make an enemy of somebody who could help him. And you know, it’s almost like he can’t help himself. It’s almost the only explanation, but there are points where you just want to shout, What are you doing? What’s the matter with you? But that’s one of the things about Poe – drive you a little nuts when you read his is that, yeah, Poe had a lot of bad luck, but he created a lot of bad luck, too. And you know, that’s one of the less attractive things about Poe.

Eri: Yeah. One example of that is when a fellow poet named Elizabeth Ellett develops a crush on him. He kind of mocks her for it. And he handles it really poorly.

Mark: He does, but so does she, you know, Ellen is a very malicious gossipy woman, who uses her New York Circles to really make a lot of trouble for Poe. You know, he handles it badly, but it could have been been over. But for the rest of his life, you know, Ellen is kind of hanging there making trouble. And he anticipates. When he’s courting Helen Whitman. With his friendship with Annie Richman. He warns them! He says you’re probably gonna be hearing from this woman or friends of this woman and they’re gonna tell you terrible things about me, and they do. By the way he’s right, she does try to make trouble, for she was a really, you know terrible enemy to have and it was one of those things where circumstances just got out of control. It’s almost a comic opera when you see – get to that point in the book and you read about that going south. It’s almost like a soap opera. Poe almost gets himself into duel, and he gets into a fight with a friend. This is what those last years were like. Poe wrote a short story earlier on called A Descent Into the Maelstrom. That’s Poe’s last couple of years. It is a descent into the maelstrom. It’s exactly what’s happening. You can see this at almost every aspect of his life, is – the poor guy. And you’re right when you said, does Virginia’s death sort of spark this? Well, the fight with Ellett precedes Virginia’s death. That occurred, and his ostracizing from the New York inner literary circles happened before Virginia’s death. But that is the period where, you know, it’s like there’s a moment where Poe (laughs) almost has it. He almost has got it. (Laughs) And that is when The Raven is published in 1845. Poe for one of the few times in his life, things are going his way. The year before, he became a very successful lecturer on the platform. He was very successful in Philadelphia and New York. He was a very good speaker, very dynamic speaker, very good reader of his own poems, and he could hold an audience. Here again, the son of actors. So he had this successful career in 1844. He’s kind of this celebrated guy on the lecture circuit. So he’s got that going for him. He’s just come off this hot streak in Philadelphia where he’s written all of these great stories like the Tell-Tale Heart, and The Purloined Letter, and The Black Cat, and The Pit and the Pendulum, The Fall of the House of Usher, and you know, everything’s kind of – he goes to New York. He publishes The Raven, and The Raven gives him this first taste of true literary celebrity that he’s never had before. And The Raven’s a sensation. It’s an overnight success, and it’s republished in every periodical up and down the coast. And he’s even become known as the Raven Man, and he’s enjoying it. He’s having a good time. This is almost the point where you hope Poe dies. (Both laugh) This would have been the perfect time. Instead of having those, then we would have been denied some really good stories. But at this point, he’s really enjoying some celebrity. He goes out and the neighborhood kids follow him at a distance and call him the Raven Man. They throw pebbles at his heels and he waits until just the right moment and he wheels around and says, “never more”, and they all go screaming off and he’s having a ball. He’s playing up to it like Stephen King plays up to it early in his career when he’s doing commercials, being the horror writer. He’s having a great time. And then he gets invited into these literary salons. And he is the darling of these literary salons. And he’s asked to recite the Raven over and over again at all of these. And he makes sure the lighting is just right, the candles are just right when he does the readings. This is where everything’s going for him. But Virginia is dying, he has this awful feud with with Ellet and it leads to his being ostracized from the blue stocking New York crowd. And his writing goes south. He doesn’t write very much after this and then he has all these these feuds, these literary feuds with people like Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. It’s a very one sided feud, because Longfellow doesn’t engage, but he accuses Longfellow, the most popular poet in America, of plagiarism. Not entirely wrong, by the way, but he does everything he can at this moment where everything is going for him. He makes sure that everything goes in reverse. In a year’s time, everything is going against him. That’s Poe. That is so Poe. (Laughs) So yeah, that’s kind of really the turning point, which is where he has this moment where finally everything seems to be going in his way, and for all the right reasons. Because he’s being lionized as a lecturer and then people are lined up to hear him talk and give these these talks on poetry and to recite his poetry. You’ve got, you know, him in New York at the center of all of the literary greats and he’s you know, he’s got the fame of The Raven. He’s got it. He’s this is the moment. This is the moment where anybody else would have built on this. And things would have gone up and up and up. But with Poe, it all falls apart very rapidly and disastrously.

Erik: Yeah. So that summer of 1849, when he starts acting especially strange. Some of that time is unaccounted for, which adds to the mystery. One of the pivotal moments that summer for him was when he visited a man named John Sartain. Would you tell us who Sartain was and why Poe met with him and what they said to each other?

Mark: Sure, you know, and it’s actually where I kind of begin the book because it’s this amazingly dramatic moment. Poe leaves New York. He says farewell to the person who is both his aunt and his mother-in-law, Mariah Muddy Clem, on June 29, 1849. And he boards a steamboat in New York, which was going to take him to Perth Amboy, Jersey. And then he was going to make a train connection to Philadelphia. Now something happens here, you know, it’s not the train that goes off the rails, Poe goes off the rails. At this point, he gets to Philadelphia. And he apparently was arrested for being drunk. He was taken to the what would we would call a night court. It was called Mayor’s Court back then. And he spends a night in jail. So he probably was drinking, he probably, you know, had had some alcohol, he probably had the usual devastating effects on him that it does. And the next thing you know, he, he charges into the studio of John Sartain. And Sartain is kind of this, he knew Poe. They had met years before, they were friends. And Sartain was an artist, an engraver. He had been born in England. He had immigrated to the United States and settled in Philadelphia. And Sartain’s life is the exact opposite of Poe’s. He had revived a engraving process, which was called the Mezzotint engraving process that he’d studied in England. Once he’d established himself in Philadelphia, the opportunities, the commissions, they just came rolling his way. Sartain never lacked for work. He was very handsome, very popular, very down to earth, very generous and Sartain and his wife Susanna had eight children. Four of them became artists. So here we are, this amazing moment where Poe charges into Sartain’s studio looking wide-eyed and desperate and at this moment you have to look at these two. If you could just freeze it for a second, if this were a movie and we could freeze this. You freeze it and you said let’s look at these two guys. Here’s Sartain. Sartain, this is 1849. Sartain is happily married, everything going for him. He is going to live to be 89 years old. He’s going to die in 1897. He’s still got a lot of life left. Poe is going to be dead in 14 weeks. When you are looking at the these two people standing here. All right. Now let’s start the movie back up again. (Laugh) And you realize, okay, now here comes Poe. He’s telling Sartain, there, you know, this bizarre account of what happened to him when he left New York. He said he was on a train. And because he had this acute sense of hearing, he could overhear men a few seats away planning to murder him. And he managed to give them the slip and to come back, and he then made his way to Philadelphia, and he makes his way to Sartain because he knew Sartain would give him shelter. He’s like a babbling paranoid person. This usually courtly, gentlemanly person is clearly disturbed so Sartain does everything he can to calm him down and tell him it’s alright, you can stay here. There’s this bizarre encounter in Philadelphia. It starts the beginning of the end. It begins the disintegration and the mystery of what happened to Edgar Allan Poe. Almost everything that happens, we have very good documentation for where Poe is during these last few months. We know there’s a lot of record about how Poe makes his way onto Richmond and all of that, and then finally heads back up north, and that’s, you know, the true beginning of the end. But each step along the way, you’re given another piece of the puzzle, and Sartain sort of gives us the first piece, because, you know, Poe is clearly agitated, but he stays in Philadelphia for a little while and Sartain sees him and a couple of days later, he’s come back to his senses. Poe has come back to his senses. Well, this is not… It’s clear to me Poe was drinking, you know, it’s clear to me because this so suits Poe’s pattern. The effects of the alcohol generally lasted a couple of days. He would have to take to his bed after he had drinking bouts. So the fact that a couple days later, he sort of returns to his senses and he tells Sartain that – he apologizes and says he was out of his head and it was all hallucinations and all of this. That very much suits the pattern, but there’s also a cholera epidemic which is raging through the country at this time and Philadelphia is panic-stricken. Now it didn’t end up hitting Philadelphia as badly as it hit some other cities, this cholera epidemic. Philadelphia actually ended up doing all right, but the city’s a little bit on the deserted side. It’s very hot, it’s summer, and Poe says he contracted cholera. We don’t know whether he did or not. If he did, he’d have known it because the symptoms of cholera are very severe. They don’t last long. You have cholera. It works its way – if it doesn’t kill you, it works its way through your system very fast. But you have very definite symptoms of cholera, not the least of which is diarrhea. So if he’d had cholera, it’s not like, oh, I don’t know whether I had cholera or not. Yeah, you know, you know, whether you had it, but whether he did or not, he obviously got treated for it, because the samples of his hair which were taken when he died, were subjected to, to a couple of major tests. And one of them shows mercury – traces of mercury. Well, they gave mercury – a medicine with mercury was very common for cholera, which is ironic because mercury is more apt to kill you than help you. It’s not a good thing to give anybody under any circumstances, but they clearly – Poe had the medicine probably in Philadelphia. So he may have had cholera and he may have been given the medicine, he probably was given the medicine for cholera either as a preventative or because he got it. And that may have also weakened his system, because if he had been drinking, and then right on top of that, he got cholera, and then right on top of that, he was given something with mercury in it. This is not a good one, two, three for your system. So by the time he leaves Philadelphia, probably an already weakened and deteriorated system had been given a pretty harsh blow. He also lands on the hard times while he’s in Philadelphia. He runs out of money. He wants to go on to Philadelphia, but he doesn’t have the funds. It’s through the help of just a handful of people who sort of get together at the end and they spread out and they raise enough money for him to get on a train and continue his journey on to Richmond. So there’s psychological stress during this period, there’s all sorts of worries on his mind about this, and he has this 1, 2, 3 of the drinking, the cholera, and the mercury. So you put all of that together and the short time he’s in Philadelphia after he leaves Brooklyn are probably devastating, and are probably inexorably putting him on the path towards where he’s going to end up in a few months.

Erik: Yeah. There are some out there, who think it’s more interesting to imagine him being murdered, and that he did indeed hear people discussing his death. And one of the theories out there is that one of the women he was courting had had three brothers who were angry about his relationship with their sister, and they were tracking him down.

Mark: Yeah, Elmira Royster’s brothers. You know, this is a very entertaining theory (laughing). I have to say, among the theories that have been put forward about his possible death, I mean, possible causes for his death. This is one which is just on the face of it is the most entertaining. It was put forward by a writer named John Evangelist Walsh in a 1998 book called Midnight Dreary: The Mysterious Death of Edgar Allan Poe. Which is a very good book by the way. It’s a terrific book until it gets to the conclusion. His research is fine and he’s a good writer. I like Walsh’s book quite a lot, but then you get to this point where he brings forth the grand theory as to what happened to Poe and it’s that, well, first off, the meeting in Philadelphia with Sartain did not happen when Sartain said it did, you know, in the early summer. It actually happened when Poe left Richmond, because that’s the only way it works, because Poe becomes engaged or believes he’s engaged to Elmira Royster by the time he leaves Richmond. In September of 1849. In order for this theory to work, he has to get engaged to Elmira Royster Shelton. Her brothers have to object to this, to the point where they will follow him, track him down and be the cause of his death. The problem with Walsh’s theory is that we have to discount somebody who is generally a reliable witness in Sartain, as far as the timing goes. But there’s also no proof. There is absolutely not a shred of proof – now now – there is proof that Elmira’s family did not approve of the marriage. But the notion that they disapprove to the point that they would think of killing him? Well, you can’t present that one without a little bit of proof. You can’t even you can’t go down that one unless you you’ve got some smoking guns in all of this and there are none. There’s not a shred of proof that he was followed by her brothers, that they tracked him down to Baltimore and Philadelphia. That they encountered him. One of the things that makes that work is that one of the ways, a cause, is that they had given him a beating. Well, Poe was under observation for the last days of his life at the hospital in Baltimore. Had he been beaten, there would have been obvious signs on the body. There would have been bruising, there would have been swelling. If he had been beaten to the point that it would have contributed to his death, there were witnesses who saw him, you know, on the street of Philadelphia and then, I mean, Baltimore and then into the polling place where he was taken afterwards. Nobody mentions this. So once again, it’s not that there’s there’s there’s bad proof or not sufficient proof for the murder theory. There’s no proof for the murder theory. It’s somewhat taken out of whole cloth. And so it’s one that I do kind of dismiss in the book because I’m a proof guy. (Laughing) Show me something here that beyond supposition that makes the murder theory work, and I just don’t see it I just do not see it. You know I’m not one to say you know I’m right – they’re wrong – this the only thing that could be, you know. I’ve been very clear when I am talking about Poe’s death that. How far I can go in what I say about Poe’s death and I was clear about this right from the start when this book, this book came out of a conversation I had with an editor at St. Martin’s. I should point out, you know, it wasn’t my idea to write this book. I’ve carried Poe throughout my entire life. I love Poe and his writing. Few writers have meant as much to me as Poe has. My wife and I have done a show for years of Poe’s poetry and stories. So, you know, but five of my books are about Mark Twain. And it never occurred to me to write a book about Edgar Allan Poe. And the Twilight Zone book that I had written for St. Martin’s had done well enough that you have that inevitable conversation where – okay, what’s the next book going to be? And It was an editor at St. Martin’s who suggested this and I wouldn’t have seen it. In fact when we were having this conversation I hit him with what I thought was my best idea, my slam-dunk can’t miss idea. Well, it missed. It missed big-time. He didn’t like it. Then he counter proposed something and I didn’t like what he was suggesting and we went back and forth like this and we were about to get off the phone and table the conversation for another day when he said, what about Edgar Allen Poe? And I said, what about him? And he said, well, it seems like you’re the ideal person to write about Poe. I didn’t see it. I said, like, well, why would you say that? He said, well, you’ve written about major horror topics with Dracula and the Night Stalker. You’ve written horror fiction. You’ve written about leading mystery topics like Columbo. You were a critic most of your professional life, as was he. Seems like you check a lot of the boxes. And I hadn’t thought of it. I said you you’ve written about a major 19th century writer with Twain, you’ve written a literary biography, seems like you’d be perfect for this and and it’s sort of like well maybe so, maybe, but the book he wanted me to write, very clear, was he wanted me to write about the mystery of Poe’s death and it’s not just a mystery, it’s a double-barreled mystery because we not only have the mystery surrounding the cause of Poe’s death, but also the mystery surrounding the missing days before Poe’s death. And I said to him at that point, whoa, whoa, whoa, whoa, whoa. You are not suggesting we write a book that will definitively solve the death of Edgar Allan Poe. You’re not suggesting we write one of those types of books that seem to arrive every two years, conclusively proving who Jack the Ripper was. That’s not what we’re talking about here, is it? And it kind of was. (Laughing) And I said, well, in the first place, this is as cold a cold case as you can possibly have. Poe dies in 1849. There’s no autopsy. There’s no death certificate. And all of the witnesses that watched him die are completely unreliable. There’s no surviving soft tissue that can be subjected to any kind of forensic test. And there’s no way to sort of advance the case. So if that’s the kind of book you want, you better find yourself another lunatic because this one’s driving away. And I said, but I’ll tell you what I will write. I’ll write you a book that examines how Poe lived through the filter of the mystery of his death. And if I can come up with a theory that I think is compelling, I will settle on it and present it but I am not going to go so far as to say I can prove it. Because I don’t think it can be proved. And I don’t even think I want it to be proved. I think there are some mysteries which are not meant to be solved. And one of the great appeals of Poe is the fact that he did leave us with this mystery of how he died. So I’m not even sure, we would lose a certain amount of romanticism if all of a sudden there was absolute 100% definitive proof as to how Poe died. So do I have a theory as how Poe died? Yes. Do I think it’s responsible, intriguing, and convincing? Yes. Can I prove it? No. And do I claim I can prove it? No. So I’m very clear about how far I can go with this book and how far I want to go with this book. I try to be tremendously responsible to what is known and more specifically to what is not known, what is unknown. If I can reasonably disprove some of the theories, I do. Rabies has always been given as a possible cause of Poe’s death. But once again, I think had there been any kind of bite, which would have been the most logical way for him to have contracted rabies, not the only, but the most logical, that would have probably been recorded at some point in the medical record. So there was not. Certainly, if you have rabies, one of the things is you cannot drink, you cannot consume liquids of any kind. And Poe was drinking water, at least we know that he was given liquids when he was at the hospital. So that alone seems to discount rabies. So do some theories get sort of knocked down along the way? Yeah, I, I try to, you know, I try to sort of limit the field a bit. But, you know, you’re still going to be left with maybe a logical explanation, but not necessarily the answer.

Erik: Why do some people believe he had rabies?

Mark: Basically because how Poe died fits, and this is one of the things which fuels the mystery, the known symptoms that Poe died with fit a staggering number of possible causes. We know he was delirious. We know he was feverish. We know that he was for times out of his head. We know that there was confusion. That can be caused by a tremendous number of things. And so you can always sort of fit your explanation to the known symptoms. Does that fit a brain tumor? Sure. Does it fit encephalitis? Yep. Does it fit heart trouble? Uh-huh. Does it fit rabies? Yeah. Those symptoms are incredibly common in a lot of different distresses. So that is another one of the problems is – there was no autopsy. And even if there had been an autopsy, it would probably have been worthless because they didn’t know how to do autopsies. Very few people know how to do autopsies in 1849 and the instruments they would have used would have been akin to a butcher’s tools compared to what they would have been using just maybe 30 years later. The Civil War was the event that really advanced the art of autopsies. We got a lot better at learning how to examine and dissect evidence, from wounds. People got a lot of practice. So Poe would have had a much better autopsy. If Poe had lived another 20 years, 30 years, he would have gotten an excellent autopsy. We would have had a death certificate. We would know a lot more. But the fact that he dies under these circumstances with the recorded symptoms being what they are, those symptoms can just fit so many different possibilities and you can twist almost any theory to that and that becomes dangerous. That becomes very, very dangerous when you’re trying to sort of put forth a theory on how Poe died. So, you know, I looked at, you know, logic, I looked at means, I looked at, you know, means and opportunity. You know, I went after this sort of like a detective case. I thought I looked at this sort of, okay, if we took all of these, say, 25 theories, and instead of treating them as theories, we treated them as suspects. Let’s look at each of these 25 as our basic group of suspects. Which suspect would we continue to have back in the room again and again because of means and opportunity and would become our primary suspect, a primary person of interest. And i think when you do that – the field drift down a lot and you sort of center down on a couple of you know – one who I think is the primary suspect and then a couple of accomplices that sort of keep coming back in and saying, you helped with this didn’t you? And so that’s kind of my theory on this. I think there is a prime suspect. But once again, if this were this imaginary detective case we’re talking about, would I take this to the DA and say you can prove it? it, it’d be a tough case. It would be a very brave DA who would take it on to a case because you’d have to make the case, not to say this is impossible by the way, but you would have to make your conviction based on a circumstantial case because there’s no hard evidence. But people have been convicted on circumstantial evidence. If you can make a chain of evidence strong enough and the chain is strong enough by the time you’re through, then you can convict on circumstantial evidence. It’s just in the realm of possibility that the case I present could be taken to court as a circumstantial case, but would I say yes that this is worth taking to? No, I’m not sure. I would feel very unsure of this. I’d feel very good about my suspect, but not so good about winning a conviction.

Erik: Sure, sure. And I know you want to keep your your own theory on what Pogue died from a surprise for readers. So I won’t ask you what you think happened, but we’ve already ruled out murder and suicide, which leaves possibilities like an illness, some kind of condition?

Mark: I think so. I think there’s a prime, and I think the suspect is in plain sight, you know. You know what the answer is. And I think that the answer is – somewhat – not only is there a suspect that’s lurking there all the time, just out of sight, but also one that has obvious accomplices and also has almost a poetic quality if it’s true. That would be almost fitting of Poe’s life that how he died would fit the pattern of how he lived.

Erik: I want to go back and ask you about those very mysterious last few days. And it basically starts after he leaves Richmond on September 27th and he eventually turns up in Baltimore which had a reputation for roughness in the 1830s and 40s, right?

Mark: Yeah and you know it also even before he gets to Baltimore – I should say you know that when I talk about unreliable witnesses it’s also contradictory witnesses that muddy the the record at every turn with Poe. The night before he leaves Richmond, he goes to see the woman he considers his fiancée, Elmira Royster Shelton. She said Poe was feverish. She said when Poe was there, he was so sickly that we were worried about him leaving the next day and in fact was worried enough to go – assumed he does he didn’t go on and take the steamer so she goes to seek him out and finds out no no he got on board the steamer. That evidence has framed an awful lot of our perception of the next few days because we think, AHA! Poe is sick when he left Richmond, you know possibly the point of becoming delirious. But Poe goes on and he sees a doctor, Dr. Carter. When he leaves Elmira, he stays, he reads the papers, he plays with Dr. Carter’s sword cane. Dr. Carter, he is a doctor. And he does not mention in his memories Poe looking – now you would think, if Poe had been feverish and sickly, a doctor would have noticed it. But he makes no mention of it. Poe then goes on to dinner with friends who then see him off to the wharf where he catches the steamer and they said, oh, he was in good spirits. He was, we had dinner, we had a good time. Right there we have conflicting evidence as – what was Poe’s condition when he got on the steamer? Was he sickly with his pulse racing as Elmira said he was? Or was he in good spirits and hale and hardy as witnesses said just an hour later? So this is always kind of the problem with Poe. You always have these kind of conflicting, as in who do you believe? You know, where do you put what stock and what information? And you got to be careful not to say I want to take the information that fits my theory the best. You got to be careful about that. So when there’s contradiction, I poin it out along the way and say, well, Elmira said this, but the doctor said this. So what do you think? I don’t know. I’m just, you know, it’s like interview the witnesses and you see where it falls. But he does get on the steamer. The steamer is heading for Baltimore, but he’s either heading for Philadelphia, where he has an appointment to edit this book of poetry for this amateur poet in Philadelphia, or he’s heading to New York to go back to Fordham. For some reason, he gets off the steamer and he ends up in Baltimore. So why did he do that is one question. When the destination was supposed to be Philadelphia or New York. Well, we don’t know. And we don’t know what condition he’s in by this point. Not one witness steps forward to say, I saw him on the boat, I saw him on the steamer. There were salons on the steamer at the time. He could have been served alcohol. Nobody comes forward to say, yes, I was drinking with Poe. I saw him. I saw him at the railing. We had a conversation. Nothing. This really is missing time. So he ends up in Baltimore and there is an election going on. And Baltimore is, you know, any Eastern town with a harbor would have a rough neighborhood, a rough reputation. You know, you have a lot of sailors and a lot of (laughs)… but Baltimore, even for a rough town, has a rough reputation in the 1830s and 1840s. In fact, they riot so often in Baltimore, it’s called mob town, and they take their rioting very, very seriously. They’re almost proud of it, you know. So Poe arrives in Baltimore, this with a reputation of being a rough town, and he arrives, we don’t know what condition, but one of the theories for the missing time is that he was cooped, and cooping is this practice that happened a lot during election time – is thugs basically would kidnap people and they would take them from one polling place to another, maybe plying them with liquor or drugs in between, and they would take them to different polling places to vote again and again for their candidate and in between they would hold them in a pen or something that seemed like a chicken coop and therefore it became known as cooping. And one of the theories for the missing days is that for whatever reason, Poe gets off the steamer, walks into Baltimore and gets himself Shanghai’d. And then he’s a victim of this election-time cooping. And he’s discovered days later, in front of a polling place, which adds to the cooping theory, wearing somebody else’s clothes, which also somewhat fits the cooping theory, because sometimes people would change clothes, so they could take them to different polling places, and they wouldn’t be recognized. So, you know, on this chilly, damp afternoon of October 3rd, he is spotted in front of this polling place in Baltimore, which is kind of a combination tavern-hotel. And was he drinking? We don’t know. You know, a cousin shows up, is called in, the cousin looks at him and given Poe’s past assumes he’s been drinking, but he has no evidence for it. And nobody else says, well, he was reeking of alcohol or anything like that. The doctor, the unreliable doctor says, no, Poe wasn’t drinking during this time. So we don’t know what was the cause of his delirium, whether this was illness or whether this was brought on by something that had happened while he was cooped, if he was cooped. But he is discovered on October 3, he is taken to a hospital in Baltimore. He lingers for a few days, and then Poe dies. And we’re not even sure the hour of his death because the attending physician John Moran changed the time of death from one account of Poe’s death to another. So we’re not even sure of that. All we really know is that sometime early Sunday morning, October 7, 1849, he stopped breathing. That’s about all we’re really certain of. And that he was buried the next day, October 8, in a small Presbyterian cemetery in Baltimore. So the mystery of the missing days and the mystery of what Poe died of is greatly complicated by what we don’t know. And with Poe, it always comes down to what we think we know, not what we actually know, but what we think we know. And as you alluded to before, Poe himself was kind of a contributor to this because he invented aspects of his biography to make himself seem younger, that he accomplished more than he had when he was younger, that he had traveled more. He borrowed experiences of his brother and worked them into his own biography and these were accepted as truths, you know, and mostly early biographies of Poe. These worked in as just -oh yeah, yep. Yep. He you know, he was in Russia and he was in Greece. He was in neither of those places (laughing). So you know Poe himself contributes to a kind of a twisted record.

Erik: That idea that he was cooped, he was in someone else’s clothing, it makes sense, right?

Mark: It’s a good theory. I mean, you know, this theory came about and sometimes the answer is the obvious one. You know, if you were to ask me, do you think he was cooped? Do you think that’s what accounts for the missing days? I’d say yes, I do. I don’t think a better theory has emerged, but as one post scholar said, it’s almost too perfect. It’s one of those theories you always question because it’s such a Baltimore solution to the problem and it fits just almost too perfectly. And once again, there are things which point towards it , and I would say there’s no better theory I think that has emerged because Poe is in Baltimore, he is found in Baltimore, he is found in somebody else’s clothing. He is there at a time when an election was going on and cooping was going on. So all of those things brought together makes cooping the most plausible theory there is. It doesn’t make it the answer, but it certainly makes it, I think, the leading candidate for what happened and accounts for the missing days.

Erik: Yeah. One of the other little mysteries surrounding his death, it has to do with what he was saying in his final days of delirium, and that included the name Reynolds over and over and over again.

Mark: Well, decades after decades of Poe scholars have tried to solve the mystery of Reynolds, the name that Poe shouted out for supposedly hours in his delirium while he was at the hospital. The one and only source for this is the ever unreliable Dr. John Moran, the young attending physician, who is our primary witness to Poe’s last hours. We don’t know how many of those hours Moran actually witnessed. We don’t know if – how much he actually talked to Poe. We do know he left behind three accounts. And the three accounts if you’ve read side by side, are astoundingly different. They’re not just a little bit different. They’re astoundingly different. You would not know he was describing the same death each time. And Moran, in his later years, went on the lecture platform, and he also fancied himself something of a writer. So, each of the accounts become more melodramatic as you read them and he starts to attribute not just a line here or there to what Poe said as he was dying, but whole dialogue, pages of dialogue that went back and forth between them supposedly. And they read like the worst Victorian melodramatic crap you’ve ever read in your life. And he even changes Poe’s dying words. He doesn’t only change the time of death, he changes the last words. (Laughs) And I would also add that both of the things he gives as Poe’s dying words are unconvincing. I think Poe would have been embarrassed to think that those were the dying words attributed to him. One of the things in this first account is he said that Poe yelled out for Reynolds and who was Reynolds? So this little detail has led to one of the great detective searches and post scholarship. Who might Reynolds be? Maybe he’s this guy, maybe he’s that guy, maybe he was this guy who was a ward person in Baltimore, maybe. No, no, no. Well, this has gone on and on, but finally, a very fine post scholar wrote an essay arguing, maybe he never said it at all. How about that? Because not only does this become a detail in one of the accounts, but then in the second account, there’s no mention of him yelling the name Reynolds in Moran’s second account. Now, if he had yelled that name for hours. Don’t you think that’s a detail that would survive into the later accounts? But he not only discards it, he then gives the name of Reynolds to a family that supposedly visited Poe, who lived near the hospital, of which there’s no record. So Moran’s testimony, you almost have to throw it out. You almost have to look at it and say – the whole record you have to call into question because there is so many differences between one, two, and three. And each one becomes a little bit more ludicrous. And I’m not sure if Moran was ever reliable in what he left us. And this is frustrating, for anybody who’s trying to work through the mystery of how Poe lived and died, because here’s the one witness we need to be accurate, precise, and reliable. And he’s none of those things. He’s wildly in the opposite camp on all these things. So I’m not so sure there is a Reynolds. Again, it’s one of these things which is attached itself to Poe, that he died screaming this name Reynolds.

Erik: It does seem so random though, you know, to make up the name Reynolds and have that something that he repeats over and over again as part of a made up story.

Mark: If it was only in the first account, I would say yes. I would say, look, he can’t be lying about this. He can’t be making this up. Don’t you think this is real? Well, then why wouldn’t it make it into the next account? It is that random. It is that distinct. So why wouldn’t you put it into the other accounts? Then on top of everything else, it would take that same very very name and then it give it a totally different meaning. It really undercuts your witness. I mean, this guy, can you imagine if we’re – okay, now, let’s take this to our imaginary case here and the district attorney has put this. Can you imagine what the defense attorney would do with this with Moran on the stand? You know, what would he do? He would tear him to pieces! It is not a jury in the world would believe in anything that came out of Moran’s mouth after this. So that’s one of the problems. Moran also, I mean, there’s this constant kind of self-aggrandizing that goes on with Moran. Moran later claims that he arranged the funeral and paid for the funeral. And then he describes the funeral. And we know what the funeral was like. He puts the funeral on the wrong day. And he says like almost half of Baltimore showed up and there was all this lamenting of this great literary man and oh, in the morning they had the body on display and there was a line – none of that happened! Poe was buried with very few people around him on a very cold day as quickly and as cheaply as possible and you know and it was two relatives who paid for the coffin. Once again, Moran just continues to prove himself to be a very, very suspicious person in all of this. And so I’m not so sure. The other thing is, had Poe called out a name. Moran had a lot of, it was a big hospital, he was the attending physician for the entire hospital. He couldn’t have been there observing Poe the whole time. So if somebody had come up to him and said, oh he was delirious and he yelled out this name, you know, he might have thought he heard Reynolds, he might have thought, I mean, he might not have even been there to have heard this and observed this. It’s one of the things that makes you want to throttle Moran in all of this, you know, because he is one of the chief manglers when it comes to establishing a clear record about at least the few days when Edgar Allan Poe was dying.

Erik: Some people think it might be in reference to a South Pole explorer named Reynolds.