When the word lynching is used in modern conversation, it conjures images of cattle rustlers confronted with Old West justice, or the racially motivated hangings in the American South, but usually Minnesota isn’t mentioned. When it is, people point to the horrible day of June 15th, 1920, when a brutal mob of 5000 lynched 3 black traveling circus workers who were accused of raping a white woman in Duluth.

On Friday, April 28th, 1882, a man in Minneapolis was hung from an oak tree, the victim of swift and angry justice from an orderly mob. It was horrible crime that many of the day agreed was so heinous and out of the ordinary, that the Minnesota courts had no real precedents or experience to draw from if a trial had actually happened. There was of course, no trial, in the quick and efficient lynching of accused rapist Frank McManus.

At four o’clock on that afternoon, Minneapolis police officer William Gleason was approached by some frantic ladies, who told him a story of a vagabond scissors grinder who had stolen away a little girl. Gleason, who had been wiling away his afternoon beat, jumped into action. He hailed a passing buggy, and valiantly jumped aboard, telling the driver to make haste to the place the women thought the kidnapper might be. As he approached 10th street he witnessed an argument taking place between another group of ladies and a man on the sidewalk. When Officer Gleason pulled up in the carriage, the man saw him and took off running down the block, and Gleason promptly made chase, barreling down the street after him. He caught up with him at 10th St and 6th Ave, and made the capture in the yard of a house near that intersection. He was promptly placed in the buggy and hauled down to the police station, where he was examined and questioned. There was blood on his vest, pants, underclothes, and hands. Soon he was arrested and charged with the rape of Mina Spears, a four-year-old girl.

Earlier that afternoon at about 2:30, young Mina Spears had asked her mother’s permission to visit Mrs. Peterson, a neighbor who lived just a short distance up the block. Mrs. Spears gave her approval, but when Mina hadn’t returned after an hour, she went to the neighbor’s house to check. Mrs. Peterson told her that Mina had never arrived at her home. Panicked and frantic, Mrs. Spears started to search the neighborhood, and came across two boys, who said that they had been with Mina earlier, when a man approached them with money and offered to buy them candy at the sweet shop. The man accompanied the children there, and bought them their candy, which they eagerly devoured. At that point the man led Mina away alone. As Mrs. Spears scoured the streets for her daughter with some other local mothers and the boys, they stumbled across the man who the boys immediately identified as the girl’s kidnapper. There, the hysterical Mrs. Spears confronted the man and demanded Mina’s return. It was at that moment that Officer Gleason pulled up in the carriage, and after the quick chase had caught him. In the meantime the virtually lifeless body of Mina was found near the wood yard where McManus would ultimately confess to having done the horrible crime. She was hospitalized and after a few agonizing days dangling between life and death, she began to make a slow recovery, at least physically, from her brutal assault.

Word did not take long to permeate through the city and the lips of its citizens were a buzz with angry conversations about the unspeakable criminal act that had just hours before been committed. The man was taken to the local police station and was immediately visited by local reporters, who were on the story in a heartbeat. They weren’t the only ones interested in what had happened; evidently news of the crime had spread through the streets of Minneapolis like wildfire, enraging everyone from the corner street urchin and prostitutes to the city’s most prominent and wealthy men. The arrested man told the newspapermen that his name was Frank McManus, originally from South Boston, but vigorously denied having done any wrong, claiming he had gotten the blood on his clothes from a fight the prior night. He couldn’t explain why the blood was fresh, however, and after being interrogated by the police later on, admitted to committing the crime to a Detective Hoy. His pants were the bloodiest item of clothing on him, and were removed for evidence.

As the evening grew darker, more and more angry citizens began gathering outside the jail, and Minneapolis Police Chief Munger, worried about a riot, decided to move McManus from his police station cell to the county jail. The growing mob, by midnight, had discovered the transfer and began to congregate with a fury that could have crumbled the county jail’s very foundations. The tension was palpable as the mass of men argued in furious tones about what they’d do if they could get their hands on him.. Finally, a group of six, in disguises, brought forward a makeshift battering ram and proceeded to smash in the locked door. “We want that man” someone told Sheriff Eustis, who had pulled duty that night to guard the jail, and had stepped in front of the mob as they tried to make their way in. “You can’t have him,” Eustis replied, but was quickly and quietly overtaken. He was whisked out of the way by some of the men, refusing to give up the keys or clues to McManus’s whereabouts. Others rushed in and swept through the cellblocks, asking inmates where the rapist was being held. One of the prisoners told them he was on the third tier, and they moved with heavy hammers to take out the thick, locked door that separated them from their target.

After gaining access, they clamored down the corridor to McManus’s cell, and found two men inside. Both of the prisoners vehemently denied being the guy they were looking for. This seemed to be a cautious mob if anything, and they went to the prison office and searched the files for any record of a physical description of an inmate matching McManus. Soon they had their information, and realized that one of the two men they had questioned matched McManus’s description; heavyset, of medium height, with a mustache and a coarse workman’s shirt. Still not quite confident in an exact match, the group of vigilantes hauled the man out of the jail, and hurried him to the home of Mina’s parents for a positive identification. The handcuffed McManus was paraded in front of the ladies who had confronted him that prior afternoon, all called from their sleep to identify him. They confirmed that this was the man they had argued with. Mrs. Spears herself cried out “That’s the man! Take him away, take him away. Oh! Those eyes, I shall never forget them!”

The leaders of the vigilante group were convinced they had more than enough evidence, and quickly decided to hang him. A large lone burr oak tree sat on the front lawn of Minneapolis Central High School, and it was hastily deemed the perfect place to display their work. Before the group escorting McManus even reached the tree, a proactive man had already shimmied up and set the rope, tied as a noose over a protruding branch. Someone asked McManus why he did what he did, and McManus denied again committing the crime. “We’re going to make a terrible example of you,” someone said, and they slipped his head through the noose. The rope was pulled tight and up went McManus, slowly convulsing and strangling as he rose from the ground. Five minutes later his body stopped moving and he was dead.

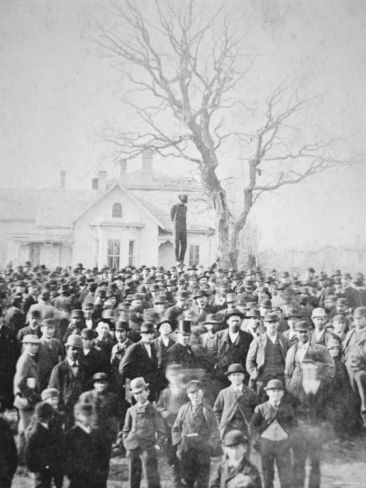

The next day around a thousand people were estimated to have visited the limp, dangling body of Frank McManus. By seven that morning people had already cut up pieces of extra rope for souvenirs, and a local photographer arrived to take pictures, including a famous one still in existence. In it, a sea of content faces with derbies fashionably cocked on their brows surround the tree, with McManus hanging above them.

The coroner at the inquest determined McManus died of strangulation. He had been pulled up by the rope, and hadn’t fallen down, so his neck didn’t break to kill him like it would have if done properly by the law . McManus’s body wasn’t buried, given instead to students at the Minnesota College Hospital for their own medical uses. Interestingly all of the newspapers of the time, even the progressive ones that despised mob justice, were keen to tell their readers that McManus deserved what he got. The Chicago Tribune summed up nicely the feelings of all of the Midwest newspapers when it wrote “If ever a crime was committed which justified recourse to mob violence in order that its punishment might be swift and sure – if any conceivable atrocity can be considered as justifying lynch law – such a crime was that of the tramp who was yesterday morning taken from the jail at Minneapolis and hanged from the limb of a tree in front of the high school building. Under the circumstances it is not surprising that public sentiment in Minneapolis and St Paul is on the side of the well–ordered mob which executed a well-deserved vengeance.”